World War II Homefront Era: 1940s: African Americans in CA Cities: A Political Force for Change

Click image to zoom in.

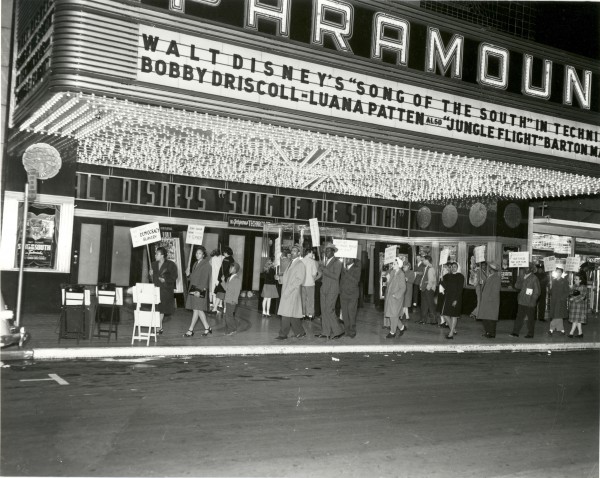

Click image to zoom in.Or view larger version. Song of the South protest. April 2, 1947. M.L. Cohen, photographer. Gelatin silver print. Collection of Oakland Museum of California.

"We want films on Democracy not Slavery"

"Don't prejudice children's minds with films like this"

-Signs carried by Oakland protesters

A racially diverse group of protesters carried signs with the above messages outside of the Paramount Theater in downtown Oakland. The year was 1947, and the protesters included African Americans and whites, women and men, youths and elders. They were protesting as part of a nationwide boycott that sought to ban the Disney movie Song of the South because of its racist messages about African Americans. The location of the protest was significant: in the 1940s, downtown Oakland was an elegant district with fancy hotels, expensive department stores, and several large-scale movie "palaces."

Walter White, the executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), telegraphed major newspapers around the country with the NAACP's opinion that the movie "helps to perpetuate a dangerously glorified picture of slavery" and "gives the impression of an idyllic master-slave relationship which is a distortion of the facts." Racially diverse groups of protesters, including African Americans, Jews, and other whites, organized to picket movie theaters in major American cities such as New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Boston. Yet the racial "harmony" demonstrated by these integrated groups of protesters was not the case in other parts of the United States at that time.

Song of the South's African American cast members were not able to join Walt Disney and the white cast members at the movie's premiere in Atlanta, because Atlanta was a segregated city. African Americans could not enter the movie theater or any other public buildings in town. In 1947, African Americans were being lynched-brutally tortured and murdered by whites-in the United States, especially in the southern states. Yet, African American individuals and organizations were investigating, reporting, lobbying, and going to court in order to stop these murders perpetrated by white lynch mobs trying to keep African Americans "in their place."

Whites in these parts of the United States used ritual lynching as a fear tactic to keep African Americans from trying to claim basic human and civil rights. Perpetrators and supporters of lynching wanted to return African Americans to the conditions of slavery. Because of this, movies that seemed to show slavery as positive and African Americans as inferior were strongly protested by African Americans and others who were fighting for human rights and civil rights for African Americans.

Oakland's racially diverse group of protesters reflected the way that major cities around the U.S. had changed due to World War II. Before World War II, Oakland, like other western U.S. cities, had a small but politically active group of African American residents who were middle class and highly educated. They felt that they should use their education and status to fight for equal access to jobs, education, unions, and political positions for all African Americans. With the large influx of African Americans during World War II, Oakland's African American population grew from 8,462 in 1940 (before the war) to 47,562 in 1950 after the end of the war-an increase of over 500 percent.

California's major cities strongly felt this population explosion. Many military bases, shipbuilding facilities, and aircraft manufacturers involved in the war effort were based in Oakland and other coastal California cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Diego. Not only were Californian African American communities suddenly politically active, but they had large enough numbers to become an actual political force for change.

A. Phillip Randolph, president of the strongest African American union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, demonstrated this new African American political power on a national scale in 1941. Randolph and other African American labor leaders represented workers who were a vital source of wartime labor. When these leaders lobbied President Roosevelt for a ban on racial discrimination in defense industries, he gave in and issued an executive order to that effect. Oakland's labor leaders brought similar influence to bear: Oakland and other California cities had a history of segregation in schools, unions, and employment, which changed somewhat in the 1940s due to the federal government's need for war workers and the organization of politically and socially active African Americans.

After World War II, however, things changed. White male soldiers returning from the war needed jobs, and they began to be hired into positions that African Americans might have held during the war. In some southern cities, returning African American soldiers were tortured and killed by lynch mobs who feared the effect these war heroes would have on the southern social order. In comparison, whites and African Americans came together in Oakland after the war to combat racism and prejudice in protests such as the one pictured above. Oakland's legacy of ongoing political activism by African Americans and cooperation between races to combat racism foreshadowed the next decade's Civil Rights movement.

Resources:

The film: Song of the South

Standards:

11.10 Students analyze the development of federal civil rights and voting rights. (11.10.1)